“Omaha” the Cat Dancer

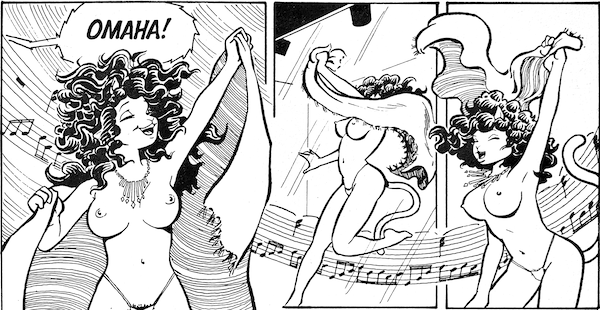

The story begins in the demimonde of struggling musicians and freelance artists meeting in the dive bars and strip clubs of Mipple City’s dilapidated ‘A’ Block. A nude dancer, stage name ‘Omaha’, is hired to perform at the opening of a new literally underground bar for the rich and powerful. Someone spikes the punch and the audience erupt in an unhinged orgy-then-riot. Omaha and her boyfriend Chuck flee, pursued by gangsters. The continuing story is a soap opera of them and their friends trying to get back to their normal lives while coping with fallout from this mess.

The comic-book series “Omaha” the Cat Dancer (1984–1995) was notable for having a lot of on-page sex scenes, and for the characters being drawn as funny animals.

Funny-animals comics

In the 1970s, American comics were typically either superhero comics from Marvel and DC, or newspaper strips, often featuring funny animals.

In 1976 Reed Waller co-founded an underground fanzine/APA Vootie, where artists experimented with new twists on funny-animal comics. This was before the term furry as we understand it today existed: comics fans talked of anthropomorphic comics (often science fiction with aliens that just happened to look like walking, talking cats), and funny animals, where characters are drawn with animal features but behave like regular people.

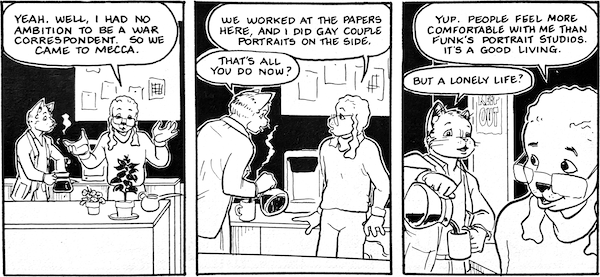

Thus Omaha, her lover and Chuck and his family are drawn as cats with human-like bodies, their friends as pigs, dogs, a bear, a goat, a bird, and so on, but they don’t act like those animals: the convention is to never acknowledge the reality or otherwise of the animal traits.

Why funny animals? My thought at the time was they make it easier to draw a collection of relatable, easily distinguished characters. In the introduction to The Collected “Omaha” the Cat Dancer volume 1, Reed Waller writes

What I believed was that humans, however carefully drawn, could never look quite natural as cartoons; they're all too obviously “imitation” people. On the other hand, a funny animal fits right in; you can hardly say a drawing doesn't resemble a “real” funny animal. As a result, maybe drama could be more effective with them, because they “belong” in the pictorial universe the way people belong in the real one.

While Reed Waller’s approach to funny animals plainly inherits from the animal people in cartoons and newspaper comic strips, the cartooniness is dialled back a bit compared to Carl Barks: they have human-like proportions and bodies, wear normal human clothes and can have human hair and facial hair, though they still have three-fingered hands.

The comic is drawn in clear black and white outline, with solid black and stippling used sparingly, and chiaroscuro reserved for special occasions. Layouts are similarly restrained: each page apart from the initial splash page has nine panels, with rare deviations to reflect moments of drama. Scene changes often happen between pages, so each page is a kind of meta-panel. Most panels are the equivalent of long shots and medium shots. It’s a straightforward, unshowy approach that makes me think of the ligne claire of the Belgian school, contrasting with comics depending on flashy colour effects and wildly variable panel layouts.

On-page sex scenes

Unlike underground comix, printed in small runs and distributed through head shops and the like, mainstream comics, sold on newsstands, were bound by a puritanical Comics Code Authority code. As printing costs came down in the 1980s and specialist comics shops arose, a new category emerged: indie comics, printed in black and white with colour covers. The ongoing Omaha series was just such an indie comic, published by Kitchen Sink Press.

Omaha started in undergrounds, which, as they defined themselves in opposition to the child-friendly mainstream comics, went a bit overboard with the adult content—hence Omaha finding herself fleeing an unhinged orgy. Reed Waller didn’t know how to continue the story after this, and enlisted his then-partner Kate Worley as writer. The story evolved in to a soap opera of separations and reunions, surprise revelations and changes in fortune—not to mention interventions from mobsters and millionaires fighting over the film from the underground orgy.

And it kept the explicit sex scenes in.

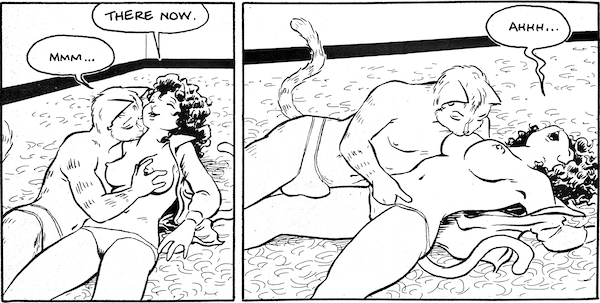

The difference from other sex comics of the time was that the sex was treated very normally. Sex was depicted with (more or less) the same pace and art style as any other part of the story, rather than in some weird impressionistic haze or as fetishistic close-ups. Kate Worley said she wanted the comic to show sex as something nice that nice people do, and I think they succeeded. We see lovers reuniting after separation, new lovers getting it on for the first time, or just colleagues having a bout while talking shop. There is some bad sex in the story as well, but it mostly happens off-page and the reader is not supposed to enjoy it.

The sex scenes caused some confusion as to how to categorize this series. Omaha was one of the titles for which Friendly Frank’s was fined for obscenity in 1988 (the case that prompted the formation of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund), but in contrast it was passed as not indecent by New Zealand’s Obscene Publications Tribunal in 1990 (see Omaha #16 letters).

It is difficult to place this series in the context of comics today. In the prose world it is now commonplace—even expected—for romance novels have on-page sex; I found it interesting rereading KJ Charles’s article on sex scenes in romance and trying to relate it to the way scenes appear in Omaha. Forty years after Omaha was published, romance and slice-of-life English-language comics with sexual themes are commonplace, mostly due to the influence of manga. Does this mean Omaha is just a normal spicy romance comic?

Not as an online comic, where the gatekeepers are not human shop owners but payment processors and advertising companies with their soulless algorithms. Comics are generally supported by advertising and hence are as self-censored as newsstands comics were. On-page intimacy is restricted to pay-walled specialists like Slipshine and Filthy Figments. There is an unsatisfactory workaround where an advertising-supported romance series has links to pay-walled erotic episodes, but they can’t be important to the story because most readers won’t see them.

Maybe as a print (only) comic, sold in the graphic novels section of your local bookshop? Just because I can’t recall any sexually explicit romance comics on the shelves does not mean they don’t exist. Perhaps there is a little space on the manga shelves between the BL and yuri titles for mixed-sex couples.

Stripping and feminism

Dancing as performance can take many forms and serve many purposes; old dances are preserved as cultural treasures even as new styles erupt from the streets or bordellos and become mainstream in turn, to the chagrin of insiders. But dance is intrinsically of the body, performance, and display—which can be at odds with concepts of modesty. How much body is too much body? How much display is too much display? The strip tease falls in to the disputed territory between entertainment and immodest display; in the comic we see different jurisdictions draw that border differently.

Display of the body, especially the female body, has long been a contentious issue for feminists. Is all erotica pornography? Is stripping pornography? Is all pornography inevitably or inherently misogynist and anti-feminist, as writers in the feminist periodical off our backs demanded? Should we reform the industry and combat exploitation by creating feminist pornography as with On Our Backs publishing erotica for a lesbian audience? Or, lurching from the general to the specific, can a comic book with strippers as main characters be feminist?

What makes a work of fiction feminist? My idea of a feminist novel is Marge Piercy writing in the 1970s about women conscious of being part of a political movement, with a lot to say about the struggle and an ending that is not so much a victory as a not-yet-defeat. Alison Bechdel’s long-running series Dykes to Watch Out For is this in comic-strip form, with her characters often espousing different strands of lesbian and feminist thought.

People also use feminist to mean works centring a woman living her life as best she can in a male-centred society, succeeding with just a hint of fantasy at how well it works out. Jane Austen’s novels are early examples. Politically this corresponds to liberal ‘individual women should have agency’ style of feminism, as opposed to the leftist ‘we must act collectively to reconfigure society so that oppression no longer exists’ style.

The Omaha series falls in to that second sense of feminist. Omaha enjoys dancing, but she is doing it to pay the rent. The dancers at the Kitty Korner and other places she works have reasonable working conditions and considerate employers (there are no pimps or traffickers in the Omaha universe). She doesn’t like being sexually harassed by punters or recognized in the streets, but overall she prefers dancing to office work. The male characters respect women’s choices and challenge sexist remarks on occasion; characters who do not are all very obviously villains. I feel the fantasy level is moderate, but not excessive. (If you want a more grounded insider’s view of nude dancing, there is a contemporary series Melody by Sylvie Rancourt.)

The male gaze

There is a phrase, the male gaze, originating in feminist film criticism, which might be simplistically generalized as meaning art is judged always on behalf of an imagined male viewer, even amongst women.

We may ask how this applies to a comic with scenes literally of men ogling women. But that’s perhaps missing the point: the audience are not really characters, just the backdrop; it is the dancers who have names and dialogue.

How the male gaze manifests in other sex comics in that women are all pretty and barely clothed whereas men are grotesques or cyphers. So Omaha gets points for having pretty men for its women to lust after (so far as we can tell given the animal heads), and for centring women’s desire in its sex scenes.

On the other hand, women characters praise Omaha’s beauty in terms of its effects on men, not themselves, there are no male dancers, and there are no women in the audience apart from servers. But (on the third hand) this is to expect Omaha’s authors to be even more ahead of the mainstream than they already were: back in the 1990s, even self-consciously sophisticated female-led sex-positivity campaigners would symbolize eroticism with silhouettes of naked women, not men.

The male gays

How queer should we expect an erotic soap to be? It will seem odd to modern readers brought up on a diet of BL and AO3, but the fact that there was a sex scene featuring Rob the gay photographer in issue #7 shocked some readers at the time (see the issue #8 letters page). I would have loved to see more men-with-men scenes, though given they had only one gay character and he was single for most of it, it makes sense there weren’t many.

An intimate situation was evolving between Chuck, Omaha and Jack in the last couple of issues, which could have lead to something had the series continued. The letters page of #24 (February 1995) contained this teasing note:

Okay, so Chuck and Jack didn't get it on this time … But you never know.

It's entirely possible that Chuck will eventually have some kind of homosexual encounter. Most people do, at some point in their lives. Maybe Chuck already has, or maybe he will in the future. If nothing else, there is a certain amount of bonding that goes on between two men who love the same woman. Whether or not that bond results in direct contact between them … well, one never knows, do one?

But, alas! that was the final issue.

Relationships aside, it would also be fun—if not too anachronistic?—to have Omaha meet male dancers. Surely some jollity could be contrived from a scene of male and female strippers comparing notes and teaching each other moves.

The issue of class

Most of the characters in the comic fall in to one of two classes:

- Freelancers and counter-culture types living hand-to-mouth, and

- Millionaires.

(We do see a few middle-class lawyers in later episodes.) The main difference between paupers and millionaires is that while everyone makes really terrible decisions, the millionaires’ terrible decisions are catastrophic for everyone, not just themselves. Charles Tabey (Charlie) is perhaps the least reprehensible, as he corrupts politicians with gifts rather than blackmail and extortion, but his wild fancies and unchecked power are still disastrous to those around him. Andre deRoc and Senator Calvin Bonner are out-and-out villains.

In the world of Omaha, what distinguishes the successful tycoon is not great cleverness or wisdom, but the corruption of elected officials and shameless exploitation. The closer to money and power a character is, the worse their morals. There are a lot of scenes with Charlie’s lieutenant Jerry making deals and whispering in politician’s ears, and it is often unclear whose side he is on. JoAnne is one of the higher earners in the stripper-cum-sex-worker community, but her ambition to score big and become a major player leads her to some very questionable actions.

Chuck is Charlie’s son, but has dropped out of college and changed his name to dissociate himself from the mess that greed and jealousy has made of his family. Omaha herself is poor but determined, and can proudly boast she hasn’t spent a dollar she didn’t earn herself. Both are discombobulated when a fortune is bequeathed to each of them. She takes up dancing again because she feels uncomfortable living off unearned income. He helps run a campaign against the redevelopment plans his father had been poised to take advantage of. They organize a blow-out New Year’s party for all their friends. But the series stopped before we really found out whether and how they managed to responsibly deal with their new wealth, or if they eventually become as monstrous as all the other millionaires.

Reading the comic

Worley and Waller’s relationship ended badly and they stopped producing Omaha in 1994. The “Omaha” the Cat Dancer series then comprised 25 issues, numbered #0 to #20 (published by Steeldragon Press and then Kitchen Sink Press), and vol 2 #1–#4 (published by Fantagraphics Books); these last four are also referred to as #21–#24. Issues #0 and #1 are by Reed Waller alone, the rest are a collaboration between Waller and Kate Worley. The #0 issue is a compilation of material originally published in Vootie and Bizarre Sex.

Kitchen Sink published The Collected “Omaha” the Cat Dancer in six volumes starting in 1987, and Fantagraphics Books reissued them in 1995. The first volume collects issues #0 to #2, plus some one-off strips originally published as flashbacks. The others collect 4 issues each of the comic, with bonus flashback stories in Volumes 3–6. Volume 6 reprints the last 6 issues, ending with the cliffhanger at the end of #24.

In the 1980s and 1990s, I was only sporadically able to find issues on sale. British law banned the import of ‘horror’ or ‘indecent’ comics, even ones that would otherwise be legal to sell; this was obviously silly, and Customs mostly allowed imports of titles like Swamp Thing and Sandman, but they seized Omaha often enough that it wasn’t really worth the risk for a comics shop to try to stock it. Instead one would go to comics conventions, where a dealers’ room would have dozens of stalls with long boxes of comics to flip through seeking issues to fill gaps. My efforts gained me #1, #2, the second Collected volume, #6–#17, #19 and #21–#24.

I did not find out until much later, but ten years after ending the series, Waller and Worley agreed to collaborate on a concluding arc; Worley died before finishing it, so her husband James Vance (Kings in Disguise) completed it on her behalf. These were collected as the final part of a new definitive eight-volume set by NBM Publishing, The Complete “Omaha” the Cat Dancer (2005–2013).

Unfortunately, all of the above are out of print. The recent Complete series is particularly hard to get, with sets of volumes 1–7 listed on eBay for hundreds of pounds, and no sign of the eighth volume with the new material. So I do not know how the story officially ends. The series I have starts after the inception of the gangster/millionaire plot (since I don’t have issue #0) and ends before its final resolution.

At the time I read it more for the romance/soap storyline than for the glimpses of Mipple City politics and business ethics. As part of writing this essay I went through and systematically read just the not-romance plot and it makes more sense when read continuously, or perhaps I just have a better understanding of local politics than I did as a young comics collector.

As for Omaha’s romance storyline, it has a certain symmetry viewed from a polyamorous, pansexual point of view: it starts with a threesome (Chuck and Omaha and Chuck’s other girlfriend) and ends with a threesome (Chuck and Omaha and Omaha’s other boyfriend). Without a definitive ending we can speculate as to how they continue to explore their connection.

Appendix. Apologies for terminology

The preferred term for variously defined groups of people varies over time, and also between the US and the UK, and also according to whether the speaker is someone related to a group or an outsider. I tend to take the line that straightforward terms like stripper should be OK because they’re only insulting if one believes that type of person is inherently bad. If this isn’t the case in the time and place you are reading this, please accept my apology and pretend I chose a different word.

Using gays as a plural noun, as in the ‘male gays’ headline above, is not these days considered correct, but I could not resist the pun.

- Updated to include an excerpt with Omaha dancing. Ridiculous not to include one from the start given ‘the cat dancer’ is right there in the title!

Posts on similar topics